Women, protest and the enduring power of folk music

- By Flora Murray

In a smoke-filled coffee house in Greenwich Village, New York, musician Buffy Sainte-Marie sang cheek-by-jowl with Bob Dylan at the heart of the US folk revival. It was the early 1960s, when youth culture was defined by restless agitation for civil rights at home and pacifism abroad. Capturing the zeitgeist, Sainte-Marie wrote her most celebrated track, Universal Soldier, in the early days of her career. In a crowded scene of polemics against the government, Sainte-Marie set herself apart by taking aim not at the White House but at the soldier himself. Of course, soldiers were conscripted and ordered by the government – but this did not rid them of personal responsibility and a choice:

He’s the Universal Soldier and he really is to blame

His orders come from far away no more

They come from here and there and you and me

And brothers, can’t you see?

This is not the way we put the end to war

The song immediately made Sainte-Marie a name in the folk epicentre of America. Its bold lyrics were covered by major artists like Donovan and were followed by a plethora of equally remarkable works which received high praise at the time of release. But despite all this, Buffy Sainte-Marie is not a household name in America in the same way we might think of Joni Mitchell or Joan Baez. After the release of Universal Soldier, Sainte-Marie was Billboard’s Best New Artist alongside The Beatles, but it was not long before she drifted out to the ‘periphery of showbiz’. Instead, her career took off abroad; audiences in Canada, Australia, and Europe seemed far more excited by her work than those in the US. Sainte-Marie always put this shift in fortunes down to the changing tides of the music industry: ‘I just thought, singers come and singers go’.

Twenty years passed before Sainte-Marie began piecing the puzzle together. After an exchange with a radio host who apologised for withholding her music in the 70s, Sainte-Marie realised something momentous: she had been blacklisted by the US government. After requesting and reading all 33 pages of her FBI files, she learned that her phone was tapped and her songs routinely suppressed. The idea that she was a ‘suspect character’ was disseminated to record companies and radio hosts. Some industry officials were even commended in letters from the White House for not playing her work.

Wikipedia will tell us it was the acerbic lyrics of Universal Soldier that made Sainte-Marie an FBI target, but she disagrees. After all, Bob Dylan’s career continued to soar after the scathing Masters of War, as did Neil Young’s after Ohio – a song written in a bout of anger following the killing of four students in an anti-Vietnam protest. Unlike these men, Sainte-Marie believes that what made her so troublesome to the authorities was her identity not only as a pacifist but as an Indigenous woman.

In the 60s and 70s the number of Native Americans in show business was exceptionally few. Of course, there were those stars who claimed that their ‘great-grandfather was a Cherokee’ – but, as Sainte-Marie says, she ‘had no choice but to be Indian’. With ‘a lot of education and a big mouth’, she campaigned tirelessly for Indigenous rights, turning down any public appearances that asked her to temper her activism. For its release in 1970 she wrote the theme song for Soldier Blue, a gritty, graphic film depicting the 1864 Sand Creek massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho people by the US army. But, rather like her subsequent releases, the film had little opportunity to make its mark before it was banned from theatres under the Nixon administration.

Despite the injustice, Sainte-Marie remains sanguine about the trajectory of her career. When commercial success evaded her in the US, she threw herself into grassroots concerts with the American Indian Movement and other activist groups. When her son was born, she joined the cast of Sesame Street, speaking on topics from breastfeeding to Indigenous languages for a family audience. Now aged 81, her public appearances and interviews portray a woman who firmly believes in the ingenuity, value, and power of her music. Her advice to young people is always to ‘find something you believe in and learn it, practise it, research it, and support it with all your heart’.

In Sainte-Marie’s case, the folk genre is the ideal conduit for her belief. It allows for a raw, simple, and historic sound that carries the laments of Now That the Buffalo’s Gone (1964) as well as the joys of Indian Cowboy in the Rodeo (1972). For the artist herself, folk music attracted her as a young woman because it was – and always has been – accessible: ‘These were songs that were 400-500 years old, and that really thrilled me as a person who doesn’t read music and doesn’t come from any formal music background.’

Indeed, the forms on which the modern genre is built owe far more to the anonymous voices of underprivileged groups in Anglo-American history – ‘navvies’, sailors, ‘Oakies’, gypsies, slaves – than they do to any formal compositions. Historically, and particularly before the nationalist folk revivals of the 1800s, folk music performers were amateurs – it was a participatory genre in which almost all members of a community could share. Forms were simple enough to be sung in choruses and passed through generations.

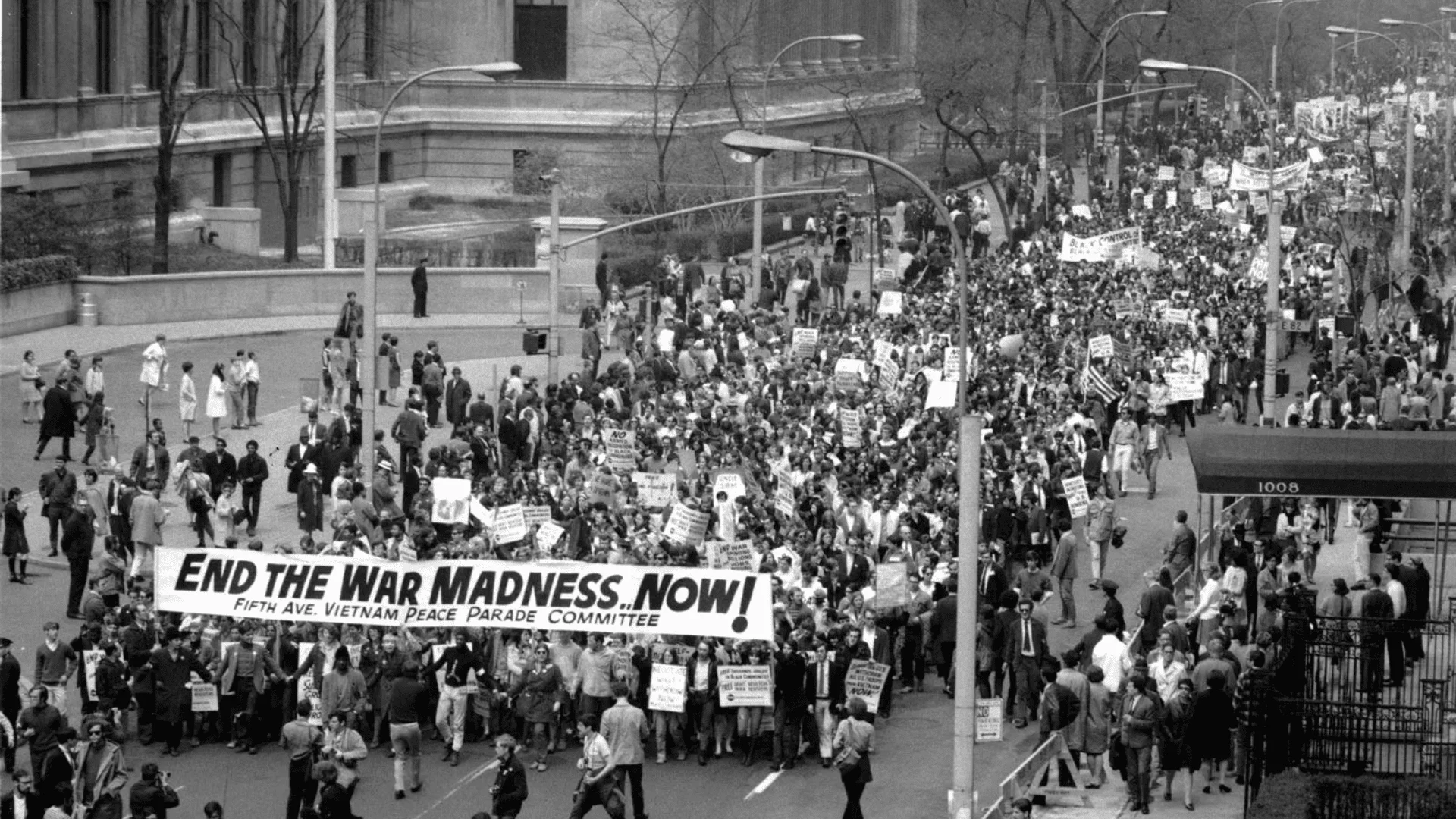

For the ‘folk revival’ artists of the 60s, these radical historical roots were easy to romanticise. The common ownership of songs, the authenticity of their sound, and the flourishing of voices otherwise suppressed spoke to young people who were tired of bourgeois middle America, its war, and its civil injustices. This era is often considered the zenith of Western folk music, where traditionally-inspired protest songs became the sound of a generation.

But what about the folk music of today? Does it still carry the same weight as a voice of activism? Paying homage to Buffy Sainte-Marie, here are four female folk artists whose music continues to be a voice of protest across the world:

- Aynur Doğan

Doğan is a Kurdish singer and musician from Turkey. In 2005, her album Keçe Kurdan was banned after a court in Diyarbakır ruled that some of its lyrics – Keçe (girl) and Ceng (battle) – might motivate women to leave their partners.

More recently, Doğan’s concert was banned by a municipal administration in Turkey for not being ‘appropriate’. Kurish songs and artists have faced haphazard censorship in Turkey since the 1980s when conflict broke out between the Turkish military and the now outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party. Doğan is now the recipient of the prestigious WOMEX 21 Artist award, which recognises the ‘highest artistic integrity in the face of political pressure’.

- Peggy Seeger

Seeger is an American eco-feminist folk singer who has lived in Britain for 60 years. Like Sainte-Marie, she discovered later in life that the US government had placed her on a blacklist, and forwarded their condemnation to governments in Europe.

Seeger’s music is a powerful reminder that folk – as a genre interested in echoing customs of the past – often reproduces misogyny. In her words, ‘women have been so thoroughly internally colonised…that we cheerfully sing songs in which we are battered, victimised, marginalised, trivialised, cubby-holed, jeered at, discarded and murdered.’ Pushing against this tradition, Seeger’s songs are anthems of Anglo-American feminism, from songs about equal pay (‘I’m Gonna Be an Engineer’) to abortion rights (‘Nine Month Blues’).

- Rim Banna

Banna was a Palestinian singer and activist known for her modern interpretations of traditional Palestinian music and poetry. She is credited with restoring old oral songs that risked being erased and forgotten.

One of these songs, Masha’al, derives from a long lineage of music in female Palestinian folklore. These tarweedeh songs were mainly sung in women-only settings like harvest seasons or births, and date back to the beginning of the British mandate for Palestine. Many deal with the departure of men who were conscripted into the Ottoman army and thus convey deep sorrow and mourning. They are often sang in jumbled, encrypted language to evade prison guards and non-native Arab speakers.

Rim Banna was one of many female Palestinian singers, like Sana Moussa, whose traditional music provides a vehicle for national Palestinian identity.

- DakhaBrakha

DakhaBrakha are a Ukrainian folk band whose unique sound is fused with punk rock – a subgenre they describe as ‘ethno chaos’. It is comprised of singer and cellist Nina Garenetska and singers and multi-instrumentalists Marko Halanevych and Iryna Kovalenko. All women trained as ethnomusicologists, making them experts in Ukraine’s musical variations.

Drawing on traditional Ukrainian folk songs, DakhaBrakha are keen to show the world the distinctiveness of Ukrainian music and culture. Borrowing a ‘white singing’ vocal style from the Hutsuls people in the Carpathian Mountains, DakhaBrakha write music about the plight of Ukrainian women and the Ukrainian identity.

See ‘Echoes from the Himalayas’ for a deeper dive into folk music in indigenous communities.