Nurturing the youth of Medellín — Gloria Bermudez and the laboratorio del espíritu

- By Lorin Bozkurt

In the heart of Colombia’s Andes Mountains, at the base of the Aburrá Valley, lies the city of Medellín – a city once notorious for being the most dangerous place in the world. Known for being recruitment grounds for infamous drug lords such as Pablo Escobar, the city fell victim to wide-spread crime at the end of the 1980s set off by narco-terrorist cartels such as the Medellín cartel. The cartel operated from 1972 to 1993 dedicated primarily to the production and distribution of cocaine and present in several regions such as Bolivia, Colombia, Panama, central America, Peru, the Bahamas, the United States and Canada.

However, it had initially emerged under Escobar’s leadership from a small-scale smuggling network located in the centre of Medellín. The cartel resulted in wide-spread violence consuming the city, including mass kidnappings, assassinations, bombings as well as the indiscriminate murder of police and law enforcement in the region. Some estimates put the total number of individuals killed at around 3,500 killed during the height of the cartel’s activities, including over 500 police officers in Medellín. To paint a picture, in 1991, the murder rate of Medellín was 381 per 100,000 residents in a population of 2.1 million.

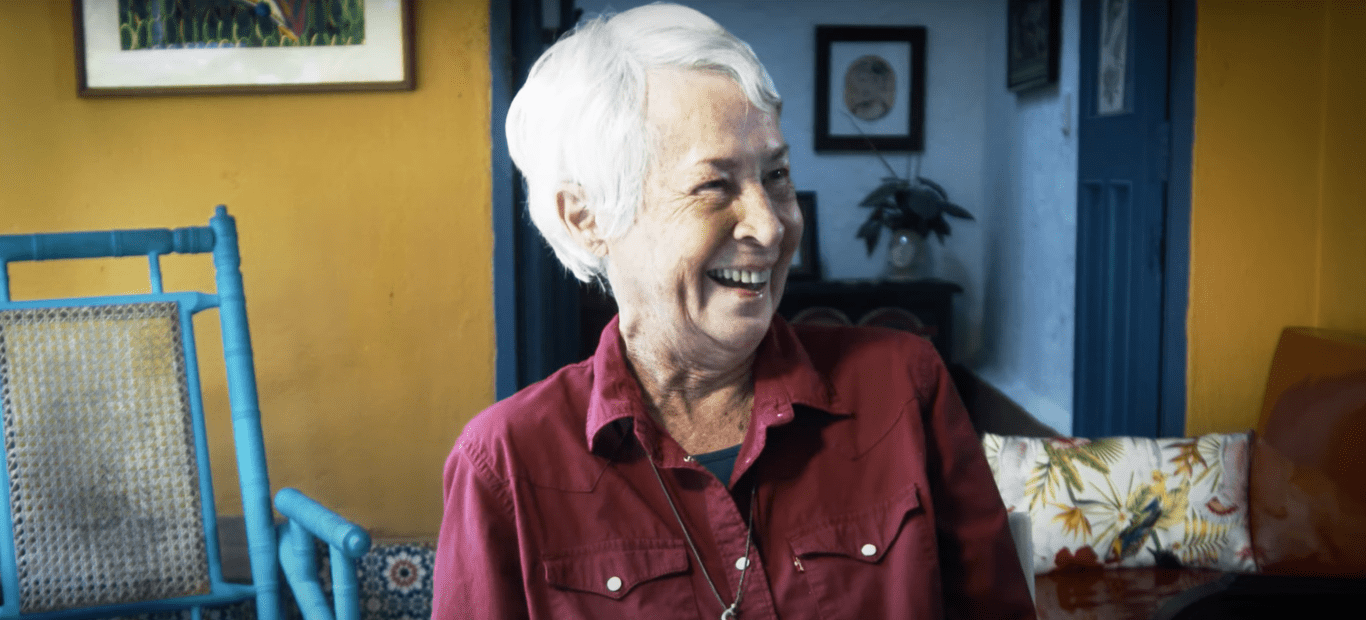

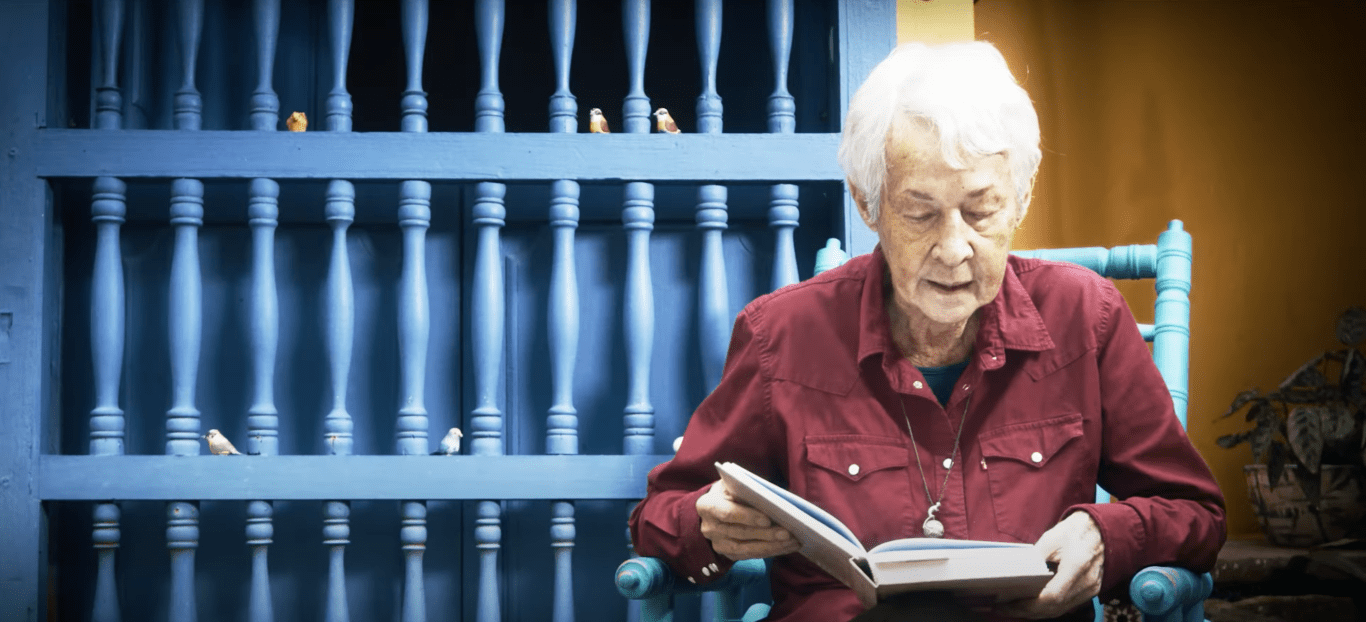

Gloria Bermudez – who, at the height of Escobar’s regime, was working away as a librarian at the University of Medellín – would aid those wounded by bullets and in armed conflict. Using the basement of the library as a place where first aid treatment was delivered, she witnessed much of the suffering and pain during these years first-hand. Learning from this traumatic experience, Gloria founded El Laboratorio del Espiritu or ‘The Lab’s Spirit’, a cultural initiative for the youth of Medellín, which aimed to transform rural areas into conducive places for dreaming – intended to act as antidote against the violence raging in these regions of Colombia at the time.

In this POLO documentary, Miguel San Joaquin – founder and CEO of POLO Women Powered stories – travels to the renowned city of Medellín to learn more about this remarkable grassroots project.

In the documentary, Gloria explains that the “Laboratorio” emerged as an initiative to make reading more accessible for young people living in rural and deprived areas, “the purpose was for young rural children to have access to reading because in rural areas there exist no libraries, and the few that do exist, contain no books”. It has since become a cultural and educational endeavour to counter the ongoing turmoil in rural areas which acted as a recruitment ground for Escobar’s illegitimate activities. The “Laboratorio” space contains numerous things, for example a music room where music teaching takes place, a ‘Colombia room’ which contains a wide range of Colombian literature, a space where workshops take place and safe spaces for young people to gather and converse. Her philosophy is that whilst a geography book may be able to nurture your mind and teach you all the different places on a map, it is only when you feed the spirit too that you may also dream of visiting those places one day.

One of the young Colombians part of this youth centre is Brian. He has been playing piano since he was ten years old and expresses his deep gratitude to the El Laboratorio del Espiritu project which he says made it all possible for him. Here, at the Laboratorio del Espiritu youth centre, is where his passion for music began and grew, leading him eventually to pursue a university degree in Music at the University of EAFIT:

“My dream has always been to become one of the best pianists and why not at international level thanks to both my University and El Laboratorio del Espiritu.”

Today, the initiative El Laboratorio del Espiritu is led by Mirella, who like Gloria, has a remarkable story herself. In the documentary Mirella, who had to have her leg amputated at a very young age, describes her experience as follows, “the disease I got was osteosarcoma which is cancer of the knee. I was asked to choose between life or death, I remember it very vividly. It was entirely up to me. And well, I chose to live and here I am”. When Gloria approached Mirella with a proposition to take part in the project and to help her lead it, Mirella immediately recognised the weight that such initiatives carries and their importance in rural, impoverished communities:

“What the Laboratorio pursues nowadays is to dignify rural areas; those rural areas that are so often neglected and that have suffered so much in the past. The extended perception is often that these areas are simply for cultivation where peasants don’t know anything and they are only useful for farming and seeds and harvesting, but behind all that there lies a beautiful story that deserves to be told.”

Many rural areas in Colombia have progressively seen transformative changes thanks to such social initiatives and investments in social infrastructure on local levels. The city of Medellín for example has seen a massive shift in crime-rate in the last two decades. Its homicide rate has decreased by 95% and extreme poverty by 66%, making it now safer than a number of US cities such as for example Baltimore, St. Louis, Detroit and New Orleans. In part, this can be attributed to the funding and emergence of local youth centres and initiatives such as those advanced by Gloria and Mirella. As Miguel himself contends: “Pablo Escobar would give to these youngsters a gun and a motorcycle, making them believe that they were now somebody, when he in fact had made of them his slaves. Gloria Bermudez, instead, is giving them a book and a space where to dream; to set them free – the perfect antidote.”