Leading Georgia’s climate change policy: an interview with Maia Tskhvaradze

- Maya Dhillon

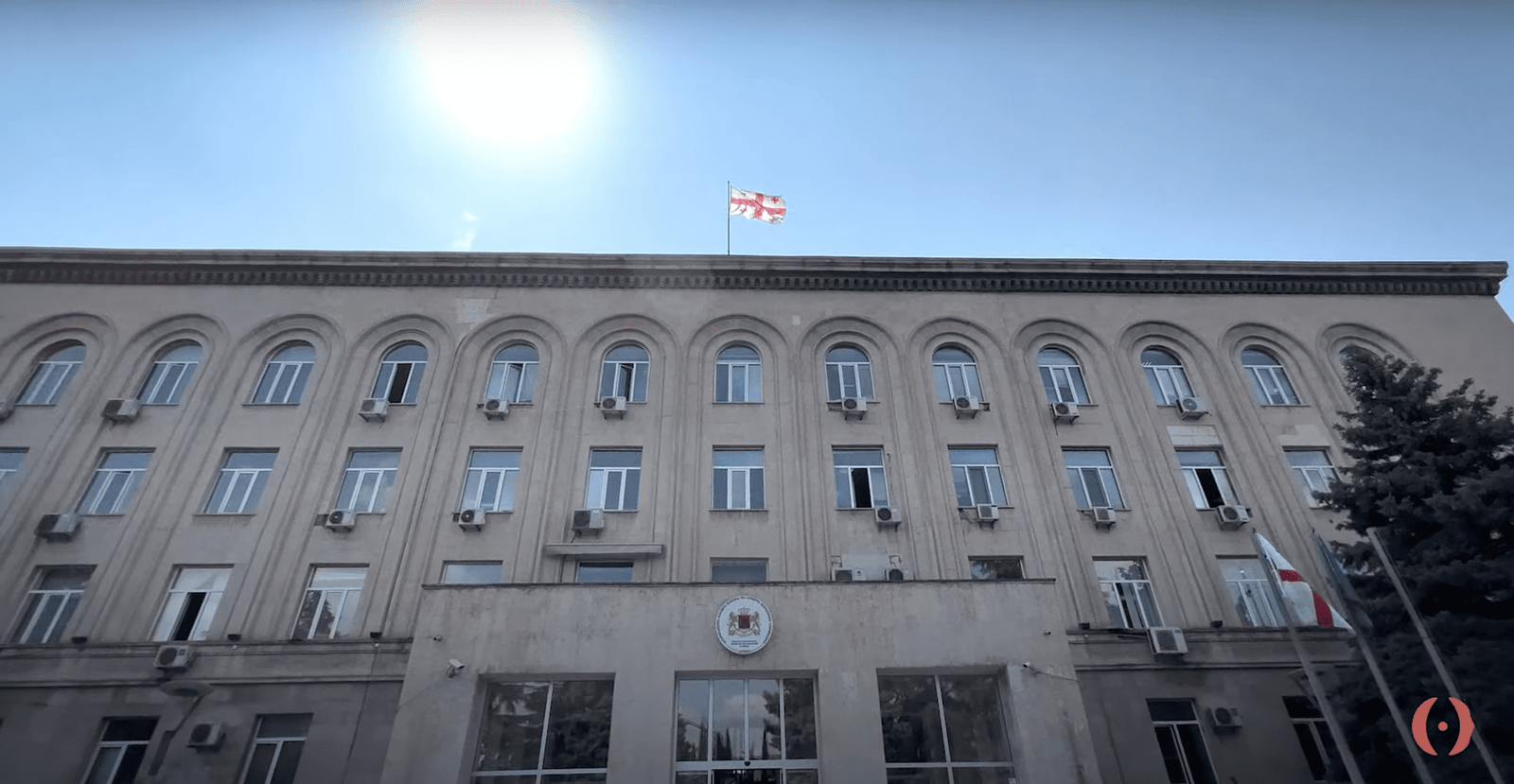

In the ongoing battle against climate change, it is clear, now more than ever, that everybody must play their part. Every single country, whether they are Annex I (an industrialised nation that is legally bound to reduce greenhouse gas emissions) or Non-Annex I (a country that is only legally bound to report their emissions, not necessarily lower them) is a cog in the machine. In that latter category is Georgia, a small yet fierce nation, hellbent on reducing their total greenhouse emissions. Their 2021 Nationally Determined Contribution sets out a strong manifesto as to what needs to be achieved: such as the mitigation of greenhouse gases by 15% in the transport, energy generation and transmission sectors (see here). Maia Tskhvaradze is part of this mighty effort to combat global warming and create an energy efficient future. Tskhvaradze is the head of the Climate Change Division at the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture of Georgia and part of the inspiring team rallying the country to attain carbon neutrality by 2050.

From the very beginning, Tskhvaradze’s story has been one of subverting expectations. Having been one of the top students at her school, she was expected to opt for the more popular and competitive courses such as International Relations or Business Administration. But, she surprised her peers when she ultimately decided to pursue a degree in Environmental Studies.

After graduating from university, Tskhvaradze worked at the Chamber of Commerce for a few years, but she felt a stirring inside her, willing her back towards her innate passion for the environment. Despite her husband’s natural concerns over a lower salary and a less developed business infrastructure, she decided to return to her roots and joined the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture of Georgia 10 years ago. She then quickly moved into the Climate Change Division, and has been head of the department for three years. Though many would consider a degree and 10 years in the industry as near expert status, Tskhvaradze humbly says that her co-workers who have been working in environmental roles for 20+ years are the true professionals. She maintains that learning is not a journey with a singular destination; there is always something more to discover and we should always look to those closest to us (colleagues, friends, family etc.) as inspiration.

But it has not always been an easy ride for Tskhvaradze. In the POLO Stories ‘G is for Georgia’ documentary, she mentions that she faced sexism early on in her career. Her appearance and attention to style have sadly called people to question the legitimacy of her intellect and professional position. She recalls a particular incident at UNFCCC negotiations where a woman from a local organisation commented that Tskhvaradze was “far too beautiful” to be in this role, questioning why she was there. Although the woman in question perceived her own comment to be a compliment, Tskhvaradze was angered by it. It was one of many instances where a woman is not allowed to be perceived as having both beauty and brains. This nearsighted binary categorisation of women is incredibly damaging and limits female aspiration; Tskhvaradze’s success has become a monument to destroying such an archaic dichotomy.

The priority for Tskhvaradze’s Climate Change Division is to make Georgia a carbon-neutral country by 2050 – a self-admittedly ambitious goal. If successful, they would be joining only a small handful of other countries: Guyana, Madagascar, Panama, Bhutan and Suriname (those last three are actually carbon-negative, meaning that they sequester more carbon than they emit). However ambitious this goal may be, it is absolutely not beyond reach and there are already significant initiatives and structures in place to ensure this. In the POLO Stories’ documentary, we see Tskhvaradze at the Cider Club Bazaleti, a zero-emissions building that is the pride of Dusheti. She considers it an embodiment of the direction that Georgia is headed: towards a more sustainable and rewarding future.

But Tskhvaradze is a realist when it comes to Georgia’s carbon neutrality goal and is totally aware of the obstacles in their way. For starters, Georgia is a Post-Soviet country operating on antiquated technology which is causing the country to lag behind in their environmental goals. Replacing these technologies would be costly, and as Tskhvaradze points out in the documentary, Georgia is a middle-income country that often relies on international financial support and donor funds in order to effectively implement initiatives.

But it isn’t just economical obstacles that Georgia faces in its race to net-zero. There is also a need for a dramatic shift in the social psyche towards energy sources and the environment. Tskhvaradze mentions the 2021 protests against the construction of a hydroelectric power plant in the Rioni Valley as evidence. Protestors argued that the proposed hydropower plants (estimated to supply 12% of the country’s domestic electricity demand) due to the high risks to the environment over the 12-month construction period. Whilst a valid claim, the final outcome of a large renewable energy source for the country would have been a positive step forwards for Georgia. Furthermore, Tskhvaradze notes that these protestors seemed to ignore the environmental damages of oil and gas as energy sources, due to their nonrenewable quality. She puts this down to an unwillingness for people to accept new methods of energy; people are naturally suspicious of what is new or unfamiliar.

In this vein, Tskhvaradze and the Climate Change Division have prioritised communication with different sectors of local communities to understand their perspectives and concerns about the country’s shift towards carbon neutrality. Some examples of the groups that the team have targeted for engagement are: farmers, ethnic minorities and youths. Regarding the last of those groups, Tskhvaradze proudly recounts an exhibition held at an electronica-music club specifically for Gen-Z to both come and talk to their own peers about climate change, as well as voice their concerns to the Climate Change Division. This ability and willingness to go out into a community and connect on their level is the initial stone throw that will eventually create a ripple of substantial change. Furthermore, Tskhvaradze wisely notes that her team can always learn something from these communities: In their offices, however hard they try, there is always going to be a disconnect between them and the reality that the general public experiences. To learn about what people actually care about takes going into the community, opening a dialogue in a comfortable environment and allowing them to lead the conversation – which is exactly what Tskhvaradze and her team are doing.

When asked about her role models, Tskhvaradze pauses. After a moment of consideration she talks about her mother, who taught her how to find the best in everything and to lead with kindness. Tskhvaradze credits her as a wealth of information who “knew how to do everything” and “did everything for everyone.” Her mother also believed that everything we do has an impact on not just the world, but the entire cosmos we exist in: the defining belief that everything single action we do has an impact on the rest of the universe, and therefore we must send out positivity and goodness only. Tskhvaradze excitedly speaks about her relationship with her own children and how, due to her busy schedule, she views time with them as precious and a privilege. She takes pride in being a non-traditional mother and joyfully remarks that her friends often say she is just as much a child as she is a mother; taking delight in the imagination and creativity that playing with her children engenders.

One may wonder: in an industry as tense as climate change, where the ‘wins’ seem far and few between, amongst seemingly endless climate anxiety perpetuated by the media and scientific communities – how does one remain positive? It is bad enough for the casual observer, but to be dealing with it on a daily basis must take its toll. Tskhvaradze admits that the stress does sometimes get to her, especially when on a global-level, things can seem very stagnant. However, she tries to “move rather than stick.” She explains that if we only focus on the negative things, the things that have already gone wrong, then we are missing the opportunity to affect the change needed. In Tskhvaradze’s eyes, we need to see the tiny steps forward as legitimate progress and will ourselves forward to fight another day and protect the earth. We are the only ones who can ultimately create a “better, greener, and happier” world.

You can learn more about Maia and her work in the POLO Stories documentary G for Georgia.