Fighting for indigenous access to safe, clean water

- By Lorin Bozkurt

What is the Indigenous Water Crisis?

In Iqaluit, the capital of Canada’s Nunavut region, climate change and lack of adequate pipeline repairs has infested what is arguably one of the most vital human resources, namely, the water. The Iqaluit city council declared a state of emergency during which air shipments of thousands of litres of bottled water were distributed to the region after evidence of fuel contamination was found in the city’s water supply. Today, the water remains high-risk, unsafe and undrinkable for the local residents of Iqaluit.

These instances of water pollution have long been affecting Indigenous peoples from all corners of the world. In the South America’s Andes mountains, India, the Philippines many indigenous communities have suffered the consequences of water scarcity due to hydroelectric, mining, and drinking water companies as well as competition over water reserves by agricultural plantations.

In the American Southwest (the ancestral homeland of the Hopi and Navajo peoples, mining by the Peabody Coal Company has almost entirely depleted the aquifer on which Native Americans rely for their water. In the Pacific northwest, PCBs and other contaminates that have been dumped into rivers by the US military have contaminated the water supply leading to fish being deemed unsafe for human consumption.

In other places such as Chile, governments have privatised water and without informing indigenous peoples with adequate information on their water rights, have sold their right to water out to others.

In places like Canada, where there is a large indigenous community, the water crisis is particularly pronounced. Cuts in funding for water infrastructure and faulty treatment systems have meant that many first Nations communities have experienced difficulties in accessing safe, drinkable water. According to one study, individuals living on First Nations reserves are 90 times more likely to be without running water than other Canadians. At the same time, the number of water-borne infections in First Nations communities is 26 times higher than the national average. According to the Council of Canadians, 73% of First Nations’ water systems are at ‘high’ or ‘medium’ risk of contamination. Despite promises from the Canadian politicians to resolve this issue, communities have grown increasingly tired and mistrustful due to years of neglect and failure of the government’s ability to meet their essential needs.

Autumn Peltier: Teen Indigenous Rights Advocate

On Canada’s Manitoulin Island – which happens to be the largest lake island in the world – Canadian teen Autumn Peltier has taken it upon herself to push for better protected water rights and ensure that her community has access to clean, safe and reliable drinking water, free from infestation from pipeline leaks and other forms of contamination. The 17-year-old has addressed world leaders at the UN General Assembly on the importance of water protection and more recently, has been made the chief water commissioner for her nation (Anishinabek Nation).

Autumn has been campaigning for water rights within her community since the age of only eight – motivated to demand conservation justice in line with traditional indigenous perspectives. In an interview with LifeGate she states that “We can drink neither money nor oil” and that “We have to do everything we can for water, even fight”.

To indigenous peoples, water is far more than a simple commodity or resource for our physical survival. It has a deeper spiritual and cultural significance where water is considered the lifeblood of Mother Earth and as such, the creator that connects all things to one another. For this reason, it must be respected – kept clean and pure and protected for the future generations of life to come. In her own words, the young indigenous rights advocate contends:

“In my culture, my people believe that water is one of the most sacred elements. It’s something

we honour. My people believe that when we’re in the womb, we live in water for nine months

and our mother carries us in the water. As a fetus, we learn our first two teachings: how to love

the water and how to love our mother. As women, we’re really connected to the water in a

spiritual way. We believe that we’re in ceremony for nine months when we carry a baby. Another

way to look at it is that water is the lifeblood of Mother Earth, and Mother Earth is female.”

Water Rights and Protection

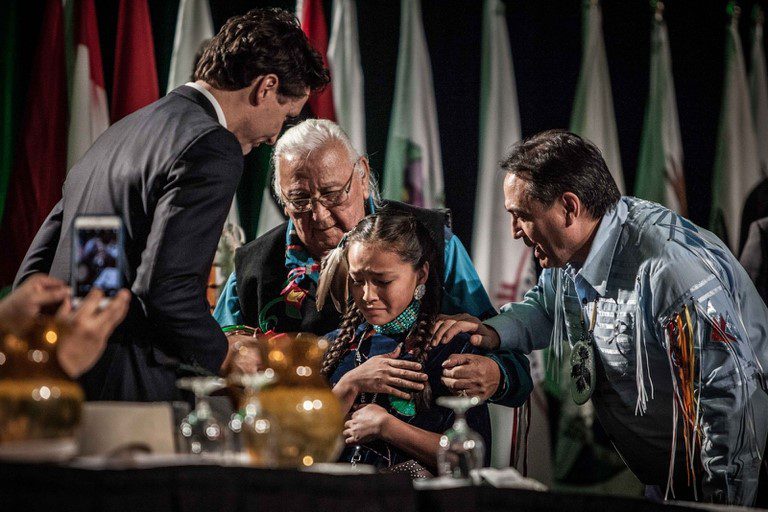

Peltier argues that the demands of Indigenous peoples in Canada are consistently ignored and minimized by virtue of their indigeneity. At a First Nations assembly in 2016 she offered Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau a cup of water and told him that she disagreed with the choices that had been made in regard to water management since they were detrimental to her community. Although Trudeau has promised changes, he has at the same time authorised the construction of Kinder-Morgan Oil pipeline. This pipeline will run from the Albetra Tar Sands all the way to the port of Burnaby on the province of British Columbia’s Pacific Coast. Some First Nation groups have since worked to oppose the building of the pipeline as it has been criticised for environmental reasons.

Charlene Aleck of the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation for example says that “this is not just our backyard, this is literally in our kitchen … it’s definitely the beginning of a long battle ahead for us”.

References

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-59253088

https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/52a5610cca604175b8fb35bccf165f96

https://canadians.org/analysis/iqaluit-water-contamination-crisis-exposes-vulnerabilities-across-canada

https://www.lifegate.com/water-defender-autumn-peltier-canada

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/autumn-peltier

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zg60sr38oic

https://www.lifegate.com/trudeau-kinder-morgan-oil-pipeline

https://www.ohchr.org/en/water-and-sanitation