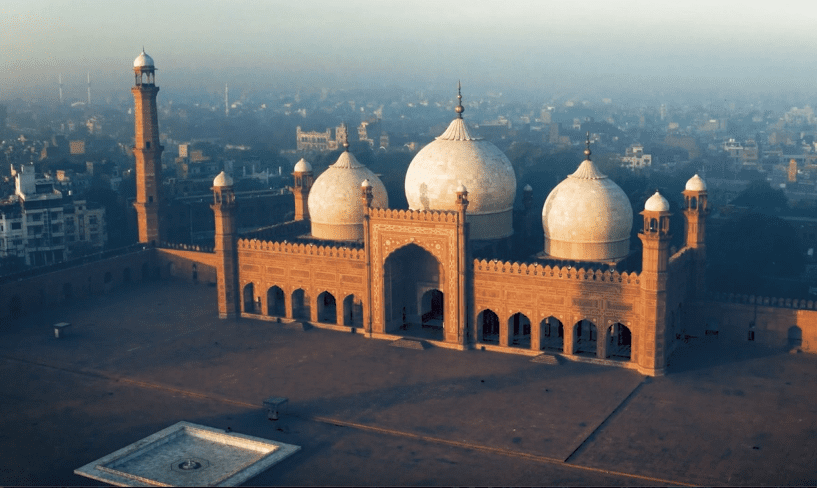

Educating the children of the red light district: Zerka Tahir and Communal Hubs in Lahore

- By Ariana Rubio

Annually and globally, it is estimated that more than three-hundred-thousand women and girls are trafficked, often for the purposes of prostitution. In 2020, Pakistan reported that approximately twenty-two-thousand women and girls were sold – sometimes by their own families – into sex slavery. Sex trafficking is a modern form of slavery which not only impacts women and girls themselves, but also those around them, especially their children. Zerka Tahir founded Communal Hub, a project which collaborates with the local NGO Social Intervention Drive and the Akhuwat Foundation, in an effort to aid such women and their children in the Pakistani city of Lahore.

In this POLO Stories documentary, Tahir identifies ‘three things’ that she believes are ‘worth fighting for’: ‘the plants, the animals and the children’. Feeling satisfied with her life, she asked herself if everyone else had access to the same opportunities to which she did. Tahir found herself perturbed by the lottery of birth, over which people have zero control. Unfortunately, some girls are born into prostitution, and others are abandoned or orphaned and subsequently sold into the illicit profession. Women who are forced into prostitution, either by the accidents of birth or harsh circumstances, often seek a better life for themselves and for their children. Indeed, Tahir was struck by the injustice of the fact that the children of ‘dancing girl[s]’ are not allowed to go to school, through no fault of their own. She resolved that ‘something needed to be done’.

Tahir took matters into her own hands and founded Communal Hubs, an organisation reaches more than ten-thousand beneficiaries in the red light district of Lahore. The organisation’s strategy, which concentrates on family and community intervention, is twofold: first, they aim to help women escape prostitution and find alternative livelihoods; and second, they aim to enable the children of sex workers to have access to education, health care and a proper childhood filled with joy.

Although, as Tahir notes, ‘our focus is and always will remain children’, they must first aid their mothers before they can aid the children. Communal Hub works together with the Akhuwat Foundation. Dr Amjab Saqib, who was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022, established this foundation in 2001 with the goal of alleviating poverty with interest-free micro loans. The Akhuwat Foundation provides financial assistance for those who come into Communal Hub’s care.

Assisting women as they break away from the strictures of forced sex work most often involves paying off loans. Brothels tend to give women enormous loans which they cannot repay, which compels them to continually offer their services. As an immediate solution to a dire problem, Communal Hubs helps these women pay off their loans. Their longer-term strategy consists of inquiring about any skills which the women may have, or perhaps aiding them in discovering any particular skills or aptitudes, which will help them establish a sustainable livelihood. This is where the Akhuwat Foundation comes in: their microfinance programme funds interest loans which enable these women to set up their own businesses.

One woman whom Communal Hub helps speaks to Tahir about her experiences as a victim of child exploitation. She recounts how her uncle brought her to Lahore as an illiterate ten-year-old child, and showed her salacious videos in preparation for her entrance into the world of prostitution. He sold her at Shahi Mohallah, a neighbourhood which is known as the red-light district of Lahore, for fifty-thousand rupees. The woman was brutally beaten; ‘my body still carries the scars of those meetings’, she says. These events are difficult for her to recall; she takes a moment to collect herself before continuing. She met a man and ‘married him because I needed support. I had no one and no support. That man got me out of there’.

Briefly, it looked as though her prospects might improve. However, after they had had children and she moved into his house, she realised that her husband and his family were also involved in the prostitution business. Her mother-in-law sent her on tours abroad. One tour in London lasted six months; the tours often took the woman away for lengths between six months to a year. She spent so much time away from her children that they stopped calling her their mother.

Gradually, Communal Hub assisted her with the payment of 250,000 rupees to her promoters for her release. Since coming under the care of Communal Hub, she explains that ‘my children have come to know me [again] as their mother’. All she wishes for is for her children to ‘study well’, ‘work’ and ‘have a status in life’; she says that if they do so, it ‘would make me forget my bad time in life’. It is thanks to the dedicated work of Tahir and the team at Communal Hub, which extracted the woman from her predicament and put her in a positive position, that this is possible.

Communal Hub is grounded in an ethic of unconditional generosity and belief. Dr Saqib, who established the Akhuwat Foundation, discusses the origin of the Communal Hub with Tahir. He explains that she came to him with ‘beautiful ideas’ of ‘serv[ing] the most disadvantaged’ people who live in ‘extreme poverty, poverty of values’. Tahir notes that, rather than asking about feasibility, reports or budgets, Saqib gave his unequivocal, unconditional support for the project.

Indeed, Tahir once asked Saqib to sanction a loan to release a woman from a brothel, and he asked her if there was any guarantee that the woman in question would not return to prostitution after they had paid off the loan. In all honesty, Tahir replied that there was no guarantee whatsoever. Saqib signed off on the loan anyway. Such unconditional support is characteristic of Communal Hub: Saqib voices his support for third, fourth and fifth chances, because ‘one day you will be successful’ in helping someone.

In terms of ensuring that the children of current and former sex workers are able to access basic needs and desires, Communal Hub gives these children medical care and an education. Within the organisation, there are two kinds of curriculum. The first is a basic educational curriculum which the rest of the province follows. The second is a ‘project-based’ curriculum, which Tahir describes as ‘peace education’. This involves an experimental approach to education which tests out the therapeutic effects of using different disciplines as tools for learning. For example, the Hub provides the children with bibliotherapy through the art of telling stories, encourages them to experiment and express themselves with a variety of musical instruments, exposes them to different artistic mediums, and gives them physical relief through the practice of martial arts.

Looking ahead, Tahir points out that Communal Hub has successfully implemented her ideas in one administrative unit, and aspires to scale up the level of impact and do so in other districts as well. She hopes that, in the future, ‘red light areas [will] be declared as conflict zones for children’, and that people realise that ‘children should not be the collateral damage’ of such areas. She concludes:

‘Every child has a right to identity, to education, to health, to recreation. But above all every child has a right to a childhood’.