Accessible, culturally-sensitive therapy for victims of domestic violence in South Africa – Ncazelo Ncube and the phola psychological organisation

- By Ariana Rubio

According to the 2022 World Population Review, Botswana and South Africa have two of the highest rape rates in the world, with rates of 92.9 and 72.1 incidents per 100,000 citizens respectively. In the late 2000s and early 2010s, South Africa’s rape rate was even higher at 132.4 incidents per 100,000 citizens. In 2009, the South African Medical Research Council conducted a survey which revealed that approximately one in four men admitted to committing rape.

In 2019, the World Health Organisation reported that African countries, particularly Kenya, Nigeria, and the Ivory Coast, struggle with unusually high rates of suicide. That said, accurate statistics on sexual violence and mental health are notoriously difficult to obtain because of different legal definitions and under-reporting. In reality, these figures are much higher. As in many other places throughout the world, it is clear that there is an epidemic of domestic violence and mental health issues in African nations.

Ncazelo Ncube, a Zimbabwean psychosocial specialist and narrative therapist who lives and works in South Africa, founded the PHOLA Psychological Organisation to combat the negative effects of trauma on families and communities in Africa in 2015. Ncube’s personal history in part inspired her to establish PHOLA. She explains that she is proud of her identity, that she is proud to be African and that she is comfortable in her own skin. However, this was not always so. As a village girl, she knows what it is like ‘to be scared, to be hopeless, to be poor’, and she aims to help those in similar positions. She summarises acutely: ‘I fight for what I believe, and I believe in women in power’.

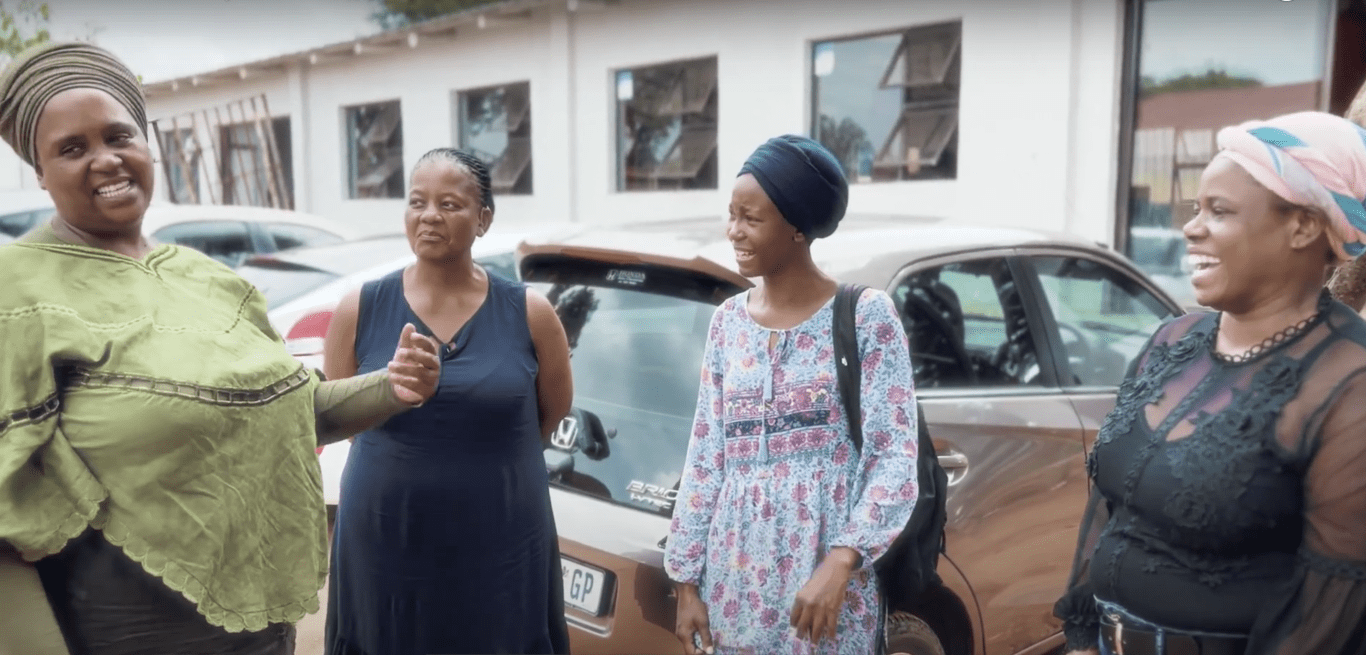

Ncube was educated at the Universities of Zimbabwe and Melbourne. She subsequently trained as a psychologist and narrative therapist, and worked at the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund in Johannesburg, South Africa, for five years. In discussion with Miguel A. San Joaquin, founder of POLO Stories, she explains that PHOLA is an initiative that aspires to advance ‘homegrown, culturally sensitive counselling methodologies’. Ncube has recruited a team of experienced social workers and psychologists who aim to create the solutions that local communities desperately need. They have designed programs which focus variously on men, women, young people, children, and entire communities in crisis.

Accessibility is one of the central tenets of PHOLA’s message and mission, and so Ncube travels around southern Africa offering free, mobile mental health services in a caravan. ‘[T]he story with the caravan’, she says, ‘is that our idea has always been to provide accessible mental health services to our communities’. Limited by low earnings, a significant proportion of people in these communities would not otherwise be able to see mental health professionals. Ncube highlights that those who normally cannot access such services are also the ‘most vulnerable people of our country’. Indeed, trauma is imbricated in the history of South Africa, where the ramifications of apartheid, the HIV pandemic, and gender-based violence reverberate in the present.

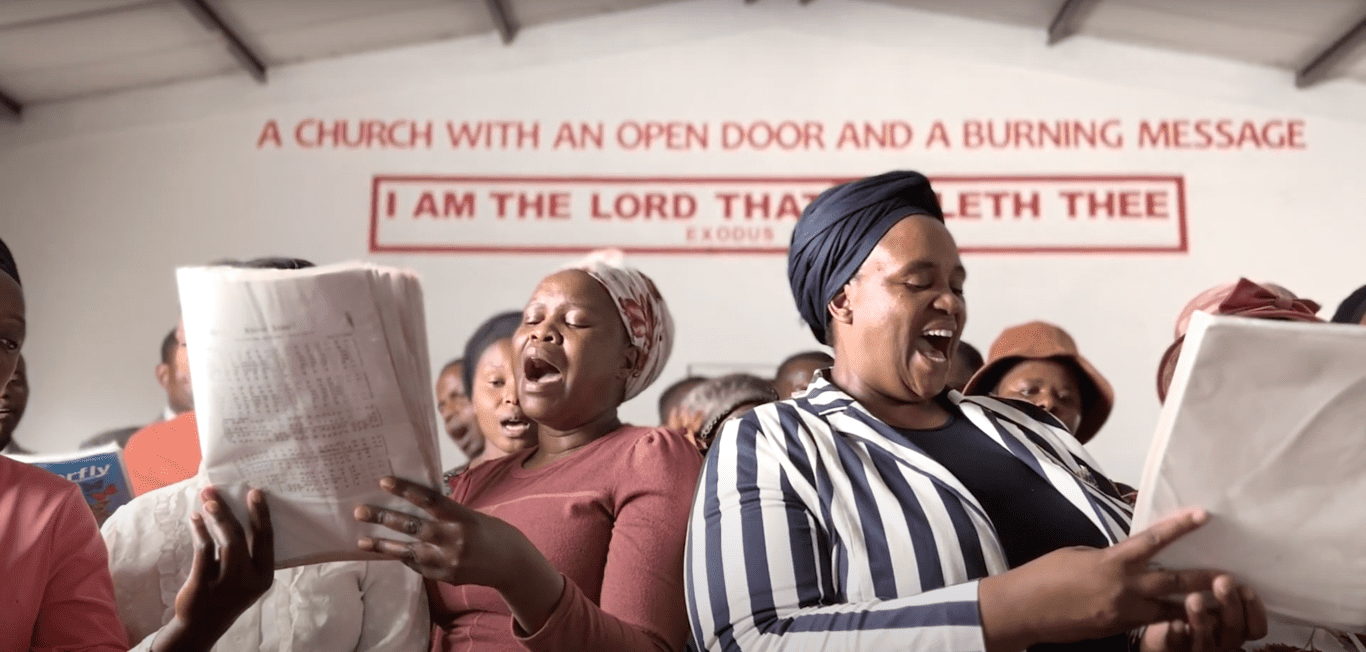

As ‘someone who’s always connected deeply with people’, Ncube identifies her reverence for togetherness as a key impetus behind founding PHOLA. She recounts her emotional distress when, as a child, she saw women selling vegetables in markets, and begged her father to buy product from each of them. Behind the measured training and coordinated response of PHOLA professionals lies the bare, human impulse to help other people. Such an impulse superabounds in the community-based societies of African countries. Ncube strives to maintain the support of ‘the village’, and enjoins the people who come to her for help to gather strength, inspiration, and encouragement from those around them.

Saliently, Ncube notes the two meanings of ‘imbeleko’ in African cultures. Initially, she was aware only that ‘imbeleko’ meant a blanket composed of animal skins which women used to carry their babies on their backs. When she began to work at the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund, however, she was introduced to ‘imbeleko’ as a concept which refers to working with indigenous communities and prizing their culturally specific knowledge and skills. Ncube unites these twin meanings of ‘imbeleko’ – first, the reassuring intimacy of carrying someone on your back and, second, giving primacy to the cultural experiences of native African peoples. In her work at PHOLA she aims to provide individual, intimate support which, rather than importing ideas of healing from the West, acknowledges and uses the restorative strategies of local communities.

In addition to addressing the urgent physical and psychological needs of victims of trauma, Ncube aspires to empower ‘black people doing things for themselves’. She sees heightened manifestations and appreciations of ‘black consciousness’ as something which all Africans should ‘internalise’ and which is ‘important for our personal evolution as well as the evolution of our continent’.

Through the ground-breaking work of PHOLA, Ncube has forever altered the lives of survivors. By 2023, the initiative intends to offer culturally sensitive mental health services to over 100,000 people annually. Despite this remarkable progress, Ncube is acutely aware that her goal of providing solutions for issues of domestic violence and mental health in African nations is an uphill struggle. It is only together – as a community, a people, and a nation – that we can come to the top of the hill and enjoy the peaceful view.