The radical history of International Women’s Day

Ariana Rubio

Across the globe, millions of people celebrate International Women’s Day annually on the 8th of March. The day inculcates an awareness of women and their contributions to and tribulations in the world.

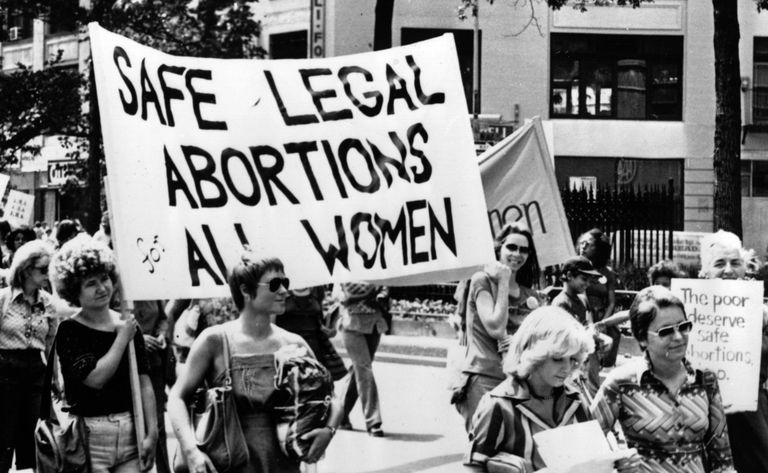

Modern celebrations include journalistic attention, corporate advertising, and giving flowers. Such performative, somewhat banal celebrations, however, are far removed from the original context of International Women’s Day, which was more protest than celebration. As the 8th of March approaches, after a year which has seen the restriction of women’s rights in various respects, it is perhaps salient to reconsider the political roots of International Women’s Day.

Radical origins

A powerful current of feminist sentiment and activism gained momentum in the political waves of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. New Zealand, for example, was the first country to grant all women the right to vote in parliamentary elections in 1893. Partly inspired by this successful campaign for female suffrage, International Women’s Day was borne of the political protests of working-class women in North America and Europe.

On the 8th of March 1908 in New York City, female textile workers held a demonstration to demand the rights to form their own trade union and to vote. Although this protest, unlike later ones, did not explicitly seek to establish a day for and about women, it nevertheless contributed to the emerging feminist atmosphere which made such a day both desirable and possible.

Subsequently, members of the Socialist Party of America organised the first National Women’s Day in New York City on the 28th of February 1909. They held the protest on a Sunday to ensure that working women could participate. The American Socialists, led by feminist and labour activists Theresa Malkiel and Leonora O’Reilly, united the suffragist and socialist causes in their calls for political and economic equality. This first National Women’s Day, which was a precursor to IWD, demonstrates that the history of the modern incarnation is imbricated with political activism.

In much the same way that the female suffrage movement in New Zealand stimulated the Socialist Party of America to observe a National Women’s Day, this Women’s Day inspired the 1910 International Socialist Women’s Conference to establish an annual International Women’s Day.

The German delegate Clara Zetkin proposed this International Women’s Day – at the time without a specified date – to one-hundred female delegates representing seventeen countries. They unanimously accepted the idea as an effective strategy for the promotion of equal rights. At the conference, Zetkin, a communist and women’s rights activist, thus described her motion:

‘The Socialist women of all countries will hold each year a Women’s Day, whose foremost purpose it must be to aid the attainment of women’s suffrage… The Women’s Day must have an international character and is to be prepared carefully’.

The establishment of International Women’s Day, then, was thoroughly collaborative and incremental. Building on the foundations laid down by their international antecedents, generations of feminist activists worked in harmony to construct a lasting edifice in honour of women.

Communist endorsement

Although International Women’s Day originated in North America and Western Europe, communist nations rapidly began to observe the holiday. On the 8th of March 1917 in Petrograd, female textile workers initiated a protest that demanded ‘Bread and Peace’ – that is, an end to the destruction of World War I, the injustice of food shortages, and the tyranny of Czarism.

It is thought that the 8th of March was chosen because of its association with International Women’s Day. This protest, in turn, triggered the February Revolution, which, together with the October Revolution, constitute the Russian Revolution. Leon Trotsky wrote:

‘23 February (8th March) was International Woman’s Day [sic] and meetings and actions were foreseen. But we did not imagine that this ‘Women’s Day’ would inaugurate the revolution’.

Following the USSR’s official endorsement, International Women’s Day spread to other communist countries in the mid-twentieth century. For example, communist Dolores Ibárruri led a women’s march in protest of Francoist fascism on the eve of the Spanish Civil war in 1936. Chinese communists first celebrated International Women’s Day in 1922, and, after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the State Council proclaimed March 8th an official holiday, with women given half of the day off.

Second wave feminism

International Women’s Day remained chiefly associated with the communist cause until the late 1960s, during which second-wave feminists began to reclaim it as a day of activism.

Where first-wave feminism focused on legal inequalities, particularly the struggle for suffrage, second-wave feminists broadened their aims of activism to include domestic and de facto inequalities such as patterns of patriarchy in the family and the workplace.

Undoubtedly influenced by the campaigns of second-wave feminists including Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, and Mary King, the United Nations began to celebrate International Women’s Day in 1975, which was proclaimed International Women’s Year. Two years later, the member states of the UN General Assembly declared the 8th of March an official UN holiday in honour of women’s rights. From then, many countries have marked International Women’s Day on the 8th of March.

Modern celebrations

In contrast to the political ardour of historic demonstrations on International Women’s Day, modern commemorations tend to be markedly less incendiary. It is not uncommon for women to wake up to a flurry of celebratory messages and social media posts, and to receive flowers and gifts on the 8th of March. Schools and universities may mark the day with a talk or presentation.

In 2022, for example, University College, Oxford, released a gallery of profile features of female students, academics, staff, and alumni, and the Saïd Business School hosted events with female entrepreneurs Asma Khan, Joana Probert, and Eleanor Murray.

Albeit far removed from the political protests of the first-wave feminists who inaugurated International Women’s Day, such celebrations are productive in that they increase appreciation and create a platform for women

Corporate commercialisation

The corporate commercialisation of International Women’s Day, however, is less benign. Vivienne Hayes, the chief executive of the Women’s Resource Centre and a key figure in the Million Women Rise March, warns that International Women’s Day is at risk of becoming a ‘bit like Mother’s Day or Valentine’s Day’, ‘instead of giving visibility to the work that women are doing around the world’.

The Million Women Rise March, in which thousands of women march in London to protest violence against women and girls, is a volunteer-run event which is devoid of corporate sponsorship. Hayes criticises the performativity of brands which jump on the feminist bandwagon by releasing t-shirts with ‘feminist’ slogans like ‘Girl Power’ and ‘Woman Up’.

On a larger scale, charges of ‘McFeminism’ were levied at McDonalds when the company turned its ‘M’ logo upside-down to form a ‘W’ in tribute to International Women’s Day in 2018. Ostensibly in the interests of female empowerment, Shell similarly changed its name to ‘She’ll’ in honour of International Women’s Day in 2020. People were quick to criticise these actions as empty symbolic gestures.

Feminist Katie Russell points out that if companies do not donate some of their profit to women’s charities and services, such gestures are merely empty symbolism. One twitter user called for McDonalds to put its money where its mouth is and pay its female (and male) workers a living wage.

Given that International Women’s Day originated, in part, from protests in support of trade unions, this criticism is especially relevant. Journalist Zarah Sultana astutely notes that:

‘in co-opting IWD, these corporations not only erase their own exploitative practices – which almost always disproportionately impact women – but also the political meaning and history of the day’.

While some thus criticise such celebrations as ineffective, performative, and avaricious, others contend that these actions raise awareness about International Women’s Day and its twin aims to promote and protect women.

A return to radicalism

If the global position of women continues to deteriorate, however, it is clear that companies should use International Women’s Day not as a promotional tool, but rather as an opportunity to effect real change.

Sarah Everard’s tragic murder by serving police officer Wayne Couzens in March 2021 reignited debates about women’s safety in the UK. Following the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, the insurgent group banned women and girls from secondary and higher education. In June 2022, the Supreme Court of the United States voted to overturn Roe v. Wade, revoking the constitutional right to abortion to which Americans had been entitled for forty-nine years.

This egregious curtailment of women’s rights across the globe suggests that the radical political heritage of International Women’s Day is more relevant than ever. It may be time to return to the combative nature of the earliest commemorations, and understand International Women’s Day not as a corporate celebration, but a protest to fight for women’s rights.