The medical mistreatment of women – past, present, and future

- By Ariana Rubio

In the early 2000s, when Dr Elinor Cleghorn was in her twenties, she began to suffer from a series of symptoms including pain, swelling, nausea and poor mental health. The academic did not know what illness was causing these symptoms, and medical doctors proved no help: they dismissed her pain as the inconsequential result of ‘female hormones’, for which nothing could be done. Vindication was mixed with sorrow when, seven years after she initially experienced symptoms, a rheumatologist diagnosed her with lupus.

This ordeal inspired Cleghorn, a freelance writer and researcher who completed post-doctoral work at the University of Oxford, to write her nonfiction book ‘Unwell Women: A Journey Through Medicine and Myth in a Man-Made World’. As Cleghorn explains in her book, this pattern of dismissal and misdiagnosis is disturbingly prevalent both in the history of medicine, and persists in present times. The face of modern medicine is blighted with the ugly boil of sexism, which manifests itself in the dismissal of female pain, male bias in medical trials, and systemic discrimination in medical institutions.

Doctors often dismiss and diminutise female pain with the assumption that this pain is psychological rather than biological. This is evident in that women are more likely than to be offered sedatives or antidepressants instead of targeted pain medication. Cleghorn, for example, writes that women are more likely than men to receive tranquilisers than analgesic drugs, and are less likely to than men to be referred for further testing in the service of accurate diagnosis. It seems, then, that, as Jackson notes, doctors crudely fill in the gaps in their medical knowledge with ‘fabricated hysteria narratives’.

Such ‘hysteria narratives’ are rooted in the ancient origins of modern medicine. In the third century B.C, the Greek philosopher Aristotle described the female body as a mutilated, inverse male body in ‘On the Generation of Animals’. From the very beginning of modern civilisation, then, women were characterised as deficient and defective in relation to the anatomical perfection of men.

Marked by bodily and biological difference, the defining trait of the female body was the womb. Aretaeus, a physician from Cappadocia who lived in the second century A.D, dehumanisingly described the womb as ‘an animal within an animal’. Indeed, the very noun ‘hysteria’ derives from the Greek word for the uterus, ‘hystera’. These sexist conceptions of the female body, which resolutely position women below men in the somatic hierarchy, reverberate throughout the history of medicine.

In the 19th century, in particular, doctors were quick to assume that female pain had emotional rather than physical causes; this assumption was likely predicated in the classical diminution of the female body. As Cleghorn neatly summarises: ‘[t]he historical – and hysterical – idea that women’s excessive emotions have profound influences on their bodies, and vice versa, is impressed like a photographic negative beneath today’s image of the attention-seeking, hypochondriac female patient’.

And, as a consequence of the dismissal of pain, this purportedly ‘attention-seeking, hypochondriac female patient’ is often forced to wait years for a correct diagnosis. For example, the average time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis for endometriosis is eight years, despite the fact that this is the second most common gynaecological condition and affects roughly 10% (190 million) of women and girls of reproductive age globally.

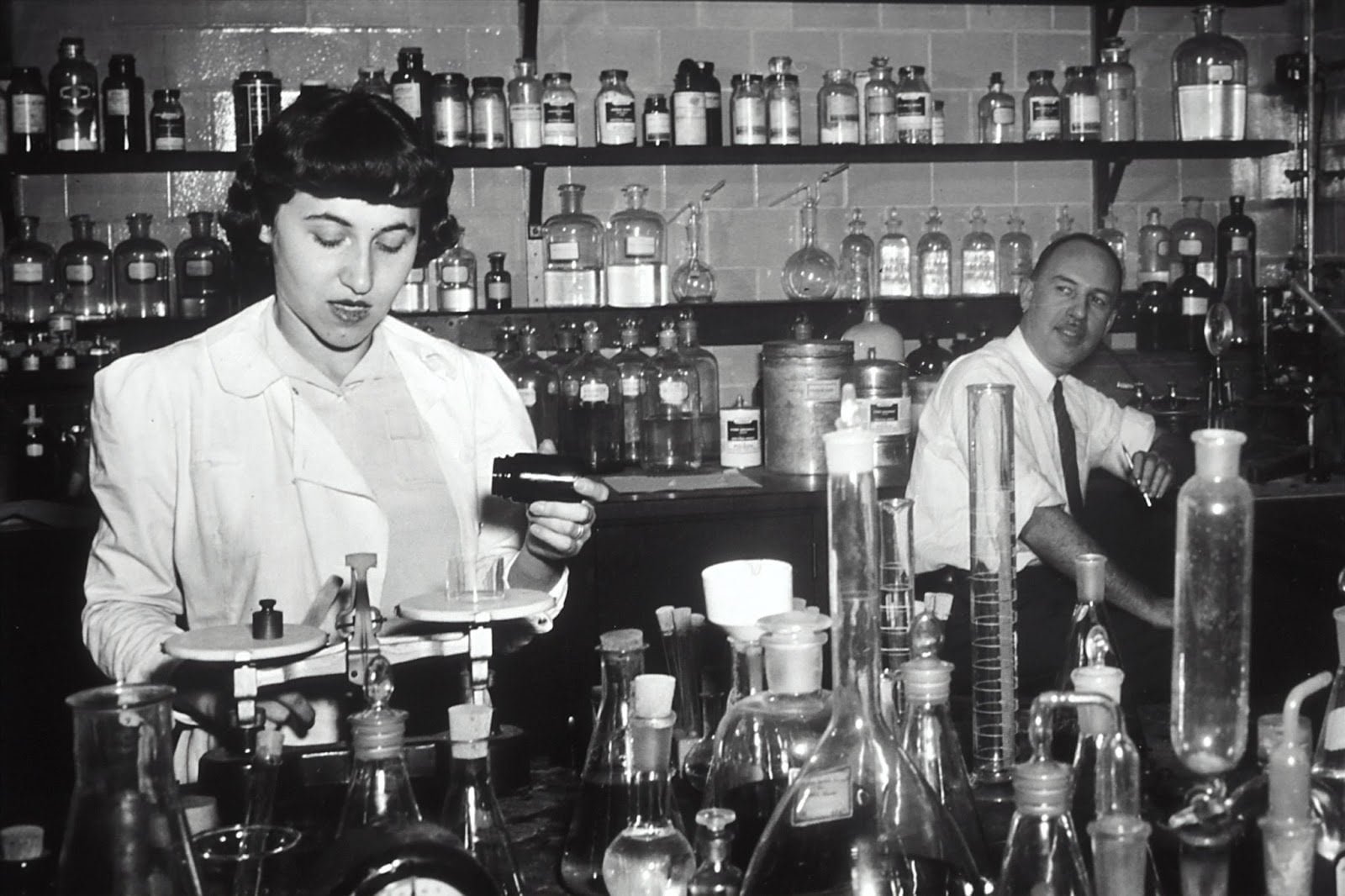

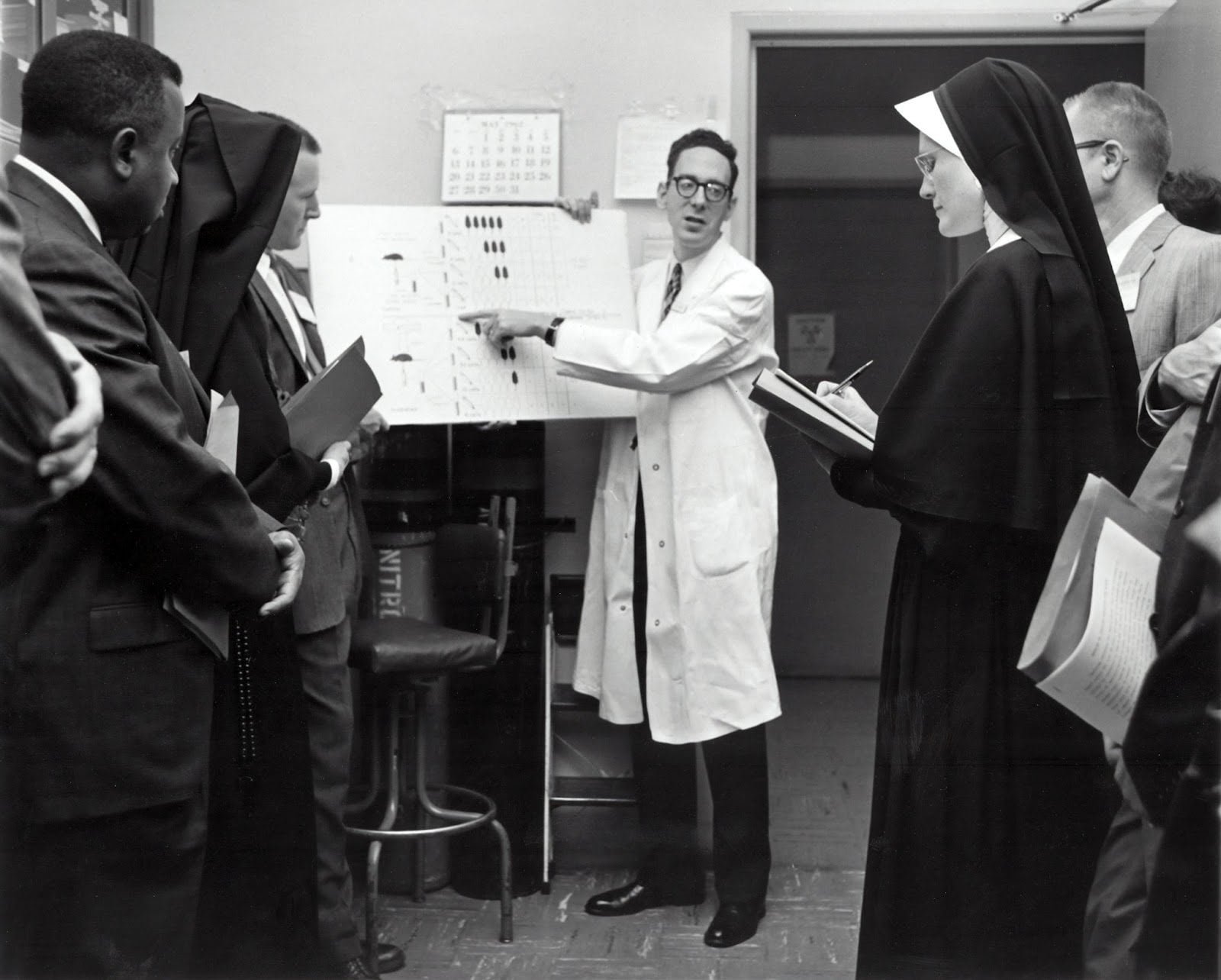

Although this pattern of dismissal and misdiagnosis is thus grounded in historically sexist ideas of the body, it is also grounded in misunderstanding. In the twentieth century, women were under-represented or not represented at all in clinical trials.

In Maya Dusebery’s 2018 book ‘Doing Harm: The Truth about Bad Medicine and Lazy Science Leave Women Dismissed, Misdiagnosed and Sick’, she chronicles several exclusions of women in clinical trials. For example, in the early sixties, researchers noticed that rates of heart disease increase as oestrogen levels drop after menopause in women. They conducted a clinical trial to determine whether hormone supplementation could mitigate this increase. Almost laughably, the study enrolled 8,341 male participants and zero female participants. Similarly, a study at Rockefeller University, which was underwritten by the National Institute of Health, analysed the effects of obesity on breast and uterine cancer without enrolling any women.

Such exclusions of women in studies which purport to investigate issues of women’s health are clearly patently absurd. But women were also excluded from studies which supposedly explored universal health problems. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, for example, which began in 1958 and looked at ‘normal human aging’, did not include any female participants for twenty years.

Sources

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/nov/13/the-female-problem-male-bias-in-medical-trials

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/western-medicines-woman-problem-180977925/

https://time.com/6074224/gender-medicine-history/

https://www.bma.org.uk/media/4487/sexism-in-medicine-bma-report.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1761670/

https://www.endometriosis-uk.org/endometriosis-facts-and-figures